Guillermo Del Toro’s Frankenstein

Guillermo del Toro’s latest vision of Frankenstein is a lush, visceral spectacle that transcends mere horror to become an operatic meditation on creation, identity and legacy. Del Toro constructs each frame as if it were a living canvas, dense with texture, saturated colour, and a sense of mythic weight. The film’s cinematography, fashion and production design all coalesce to give new life to a familiar story, yet one that unmistakably bears the director’s imprint.

From the outset, the look of the movie commands attention. Cinematographer Dan Laustsen bathes the gothic architecture in rich reds, deep emeralds and shadows so dense they seem tactile. One sequence in the laboratory dissolves the boundaries between flesh and machinery: shot through oblique angles, the lighting suffuses the assembled cadavers and metal tools in a sickly green glow while crimson fluids drip in pools. The effect is simultaneously clinical and uncanny, a world where science has become ritual and creation is revealed in equal parts beauty and abomination.

Fashion helps anchor the characters in an era that feels both historic and hyper-stylised. Victor Frankenstein, played by Oscar Isaac, is dressed in tailored frock-coats and waistcoats that hint at 19th-century formalism, yet the fabrics shimmer with unnatural sheens and the embroidery suggests alchemical symbols more than aristocratic lineage. This Victor walks the line between scientist and sorcerer. The creature, portrayed by Jacob Elordi, is conceived with the tragic elegance of a marble statue brought to gory life. Scarred skin appears almost translucent under the light, threads of deep purples and bruised greens lace the wounds, while voluminous hair drapes like a mantle of shame and power. The wardrobe avoids cartoonish horror tropes in favour of a hybrid, half-regal, half-ruin.

There’s a pivotal scene where Victor assembles the body parts of the creature that sums up del Toro’s ambition: it is filmed not in jerky cuts but in lingering takes, giving space for the unsettling physicality of the act. Splayed limbs, surgical tools, motes of dust in the beam of a single lamp, all captured not to shock but to mourn. The cinematography zooms out to reveal the room’s full height, the walls lined with relics of the war-dead, metal shelving dripping with tools, pools of chemical mixture reflecting Victor’s distorted reflection. The fashion, the art direction, the lighting all write in the same language of creation’s hubris.

The visuals are enhanced by the designer set spaces: cathedrals of decay with vaulted ceilings, corridors lit by lanterns whose flames flicker like the beating heart of ambition. The creature’s awakening happens in a ruined chapel; shards of stained glass scatter across fallen pews, the stone walls pillaged, ivy creeping in. It feels mythic, like the wound of the modern Prometheus laid bare. Within this world, the creature is not simply monster, but inverted deity, alight with grief, knowledge and silent fury.

In a notable sequence, Victor presents his creation to his patron Heinrich Harlander, played by Christoph Waltz, in a grand hall that resembles royal court chambers gone mad: crimson drapes, golden candelabras, mannequins draped in surgical gowns set as visitors. The camera glides through the hall as if performing a waltz, catching Victor’s reflection in mirrors darkened by age. The creature stands motionless, framed like a classical statue, while society spectators orbit him in hushed awe and terror. The fashion here underlines the spectacle: black suits of fine cut for the elite, but Victor’s own garment carries rivets and seams like surgical scars, blurring the lines between tailor and torturer.

What makes the film so compelling is how these elements serve its emotional core. Del Toro has been clear that he did not make a horror film per se, but an emotional story about being father, son, creator, creation. That sensibility is embedded in the visuals. Close-ups of the creature’s eyes ravaged with question, the trembling of Victor’s hand reaching for new life, the seam between body and machine, all photographed in slow, elegiac shots. When the two characters finally meet and speak, the silence around them throbs like a chamber piece; the costumes and sets seem to recede, letting the heartbreak carry the weight.

One of the film’s most powerful sequences sees the creature reading Victor’s diary by candlelight, shadows dancing on the page as crumbling walls fall behind him. The shot holds just long enough to let the fashion echo: his simple tunic is stained but elegant, torn yet dignified. The praxis of creation giving way to suffering is captured in the way the camera lingers on a frayed cuff or the way the light flickers over a wound. It is rare for costume detail to speak so much of character arc, here it does.

Cinematically the film never settles for comfort. Wide-angle lenses exaggerate the height of staircases, the depth of halls, making human figures appear diminutive against their own ambition. Handheld moments emerge when the creature lashes out or Victor collapses, juxtaposing grandeur with instability. The fusion of practical effects, rivulets of blood, bubbling vats of chemical reagents, with digital augmentation ensures the world feels grounded even as it becomes mythic. Del Toro’s insistence on real sets and real materials anchors the visual spectacle in physicality.

The fashion and set design do more than beautify, they enact the film’s interrogation of hubris. Every lavish garment has a tear, every polished corridor hides rot, every refined tool echoes executioner’s blade. The creature’s movement, graceful yet contorted, reveals his dual nature: part angel, part executioner. His costume design, while fittingly monstrous, preserves something of the human beneath, stitch lines, prim tailoring beneath the gore. Photographed in silhouette against a steel-blue dawn, the creature looks less like a horror archetype and more like a tragic monument.

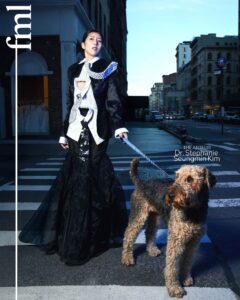

FML creative director Reinhardt Kenneth was honored to be able to attend the premiere back earlier in the month and witness it firsthand at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. Experiencing the film in that setting, surrounded by the grandeur of the museum and the energy of the premiere, amplified the power of del Toro’s visuals, fashion and cinematic world. The lingering shots, the textures, the interplay of light and shadow, all came alive in the communal space, making the film’s emotional resonance feel even more profound.

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein is a feast for the senses, not merely for shocks, but for the way its visuals, fashion and cinematography merge into an immersive rite. It challenges the viewer to feel rather than scream, to examine the stitched seams between creation and destruction, and to remember that monsters are made not born. You walk away from the film changed, carrying the image of the creature’s eyes, the shimmer of the laboratory lights, the weight of a coat heavy with ambition. In del Toro’s world, every detail matters, and here the visual craft bears witness to the broken promise of life.